A guest post by Sandy Rushton, People Powered Retrofit. Originally featured on Medium.

In the Energise Manchester project, the project partners will work together to develop novel, community-based approaches to energy advice using Snook’s expertise in the area of Behaviour Change and Service Design to guide this process.

Behaviour Change methodologies have been used to inform the design of a range of public health initiatives, from the NHS’s partnership with the DVLA to boost organ donor sign-ups to the Beat the Street campaign, getting local people walking.

Behaviour Change methodologies have also been used to help residents to reduce energy use, for example in the Share the Warmth campaign in Kent and Medway. In developing Energise Manchester, Ellie Kuitunen’s work in applying Behaviour Change methodologies to retrofit was informative, as was Greater Manchester LCEA’s 2011 report “The Missing Quarter: Integrating Behaviour Change in Low Carbon Housing Retrofit”.

Starting to learn about Behaviour Change

As I mentioned in my introduction to this blog, I’m a Behaviour Change novice. My background in Instructional Design and Service Design has given me experience in adjacent disciplines, but before diving into a project that was centred around Behaviour Change Design I wanted to get a better understanding of the foundational principles for this design discipline.

To help me get to grips with the principles we’d be using on this project, I completed the Foundations of Public Health Practice: Behaviour & Behaviour Change course from Imperial College London on Coursera.

A short history of Behaviour Change

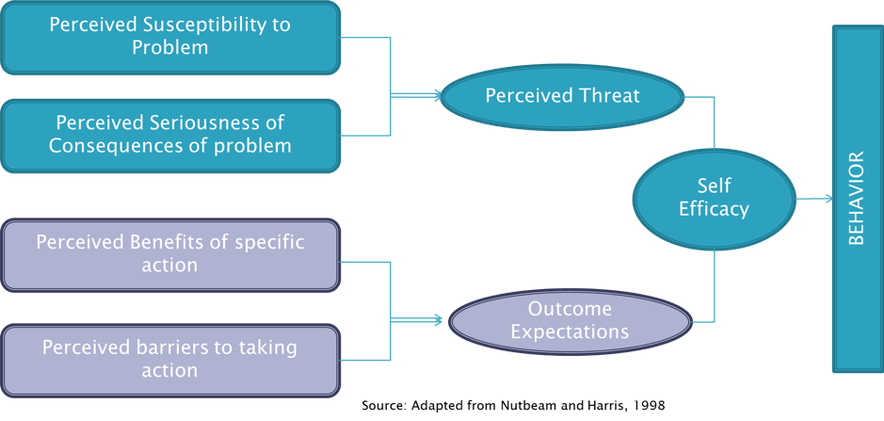

The first module of the course outlines the history of Behaviour Change principles and some of the key concepts that underpin this discipline. We first reviewed the ‘classic’ public health approach to Behaviour Change: the Health Belief Model. This model is based on value expectancy theories, which propose that there are two factors which influence behaviour: the value placed on a given behaviour’s outcome, and the likelihood that the behaviour will result in the outcome. The Health Belief Model introduces another factor, too: ‘self-efficacy’. This refers to a person’s confidence to carry out the behaviour. This is a widely used model in public health policymaking.

We then looked at Social Cognitive Theory, which adds a person’s environment into the Behaviour Change model, and the Theory of Planned Behaviour which places a greater focus on the intention of a person to carry out a behaviour.

I won’t go into detail about these different approaches to Behaviour Change here, but my main takeaway from the history of different approaches was that our understanding of Behaviour Change has become more nuanced over time and eventually included a wide range of factors that influence behaviour. However, with this added nuance these models also became more complex and, so, weren’t well placed to support public health professionals or policy-makers to take action to change behaviour.

MINDSPACE (2010) was an attempt by the Institute for Government to introduce these Behaviour Change approaches into policy-making and encourage evidence-based policy development. MINDSPACE is an acronym that stands for:

- Messenger — We are heavily influenced by who it is that delivers information.

- Incentives — Our responses to incentives are shaped by predictable mental shortcuts, such as strongly avoiding losses.

- Norms — We are strongly influenced by what others do.

- Defaults — We ‘go with the flow’ and choose pre-set options.

- Salience — Our attention is drawn to what is novel and seems relevant to us.

- Priming — We are often influenced by subconscious cues.

- Affect — Our emotions shape our actions.

- Commitments — If we promise to do something, we try to deliver on it.

- Ego — We act in ways that make us feel better about ourselves.

These 9 factors should be considered when developing policies. An even more simple version of this is EAST (2014): Easy, Attractive, Social, and Timely.

At this point, I was starting to understand how Behaviour Change approaches could actually be used to design something. But these factors were still somewhat removed from the actual activities that an individual, organisation, or government might take to influence Behaviour Change.

Moving from theory to implementation

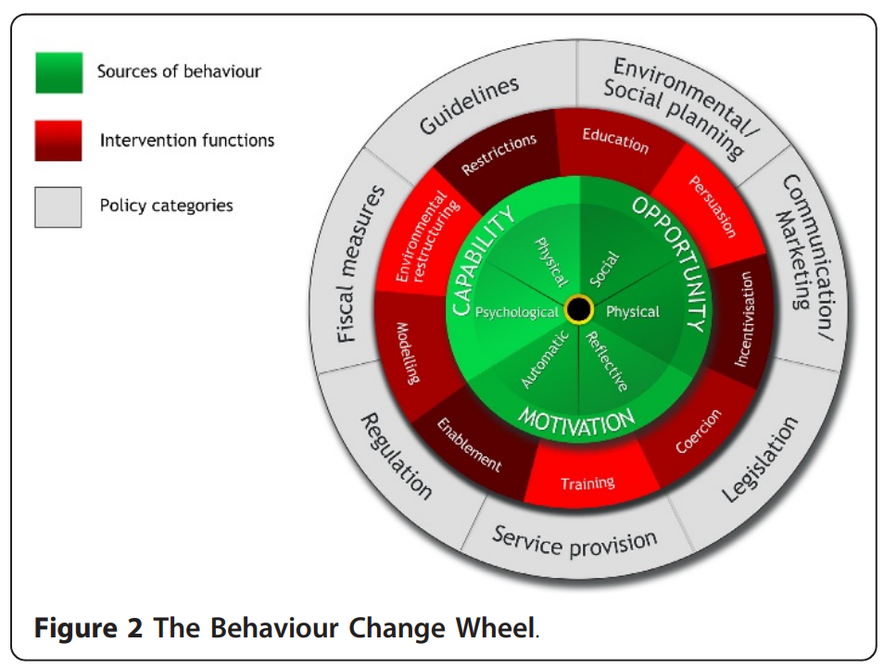

The second module of the course addresses this question, as it looks at how we can use Behaviour Change models to analyse behaviour and affect change. The main focus is The Behaviour Change Wheel methodology, which is a “practical guide to designing and evaluating Behaviour Change interventions and policies”.

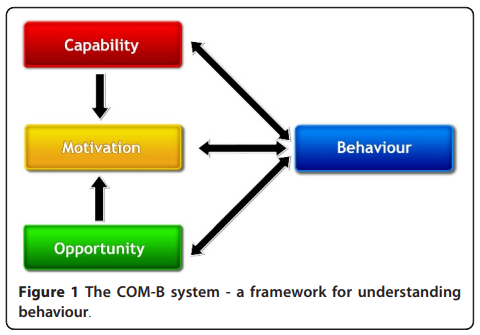

The methodology starts with a diagnostic approach, defining the problem that is trying to be solved, the target behaviour, and the target population. The COM-B approach is used here to identify barriers to a target behaviour. COM-B stands for Capability, Opportunity, Motivation and Behaviour.

For a target behaviour, the model invites you to ask:

- Capability: Is your target audience capable, physically and psychologically, of carrying out a behaviour?

- Opportunity: Do they have the physical and social opportunity to do it?

- Motivation: And are they motivated to do it, both automatically (as in, by habit) and upon reflection?

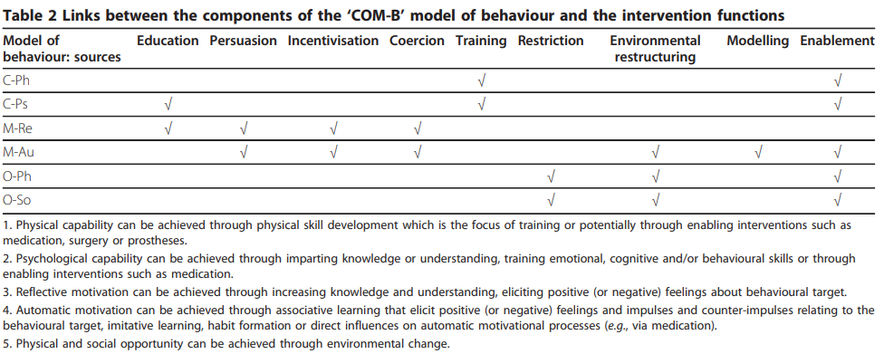

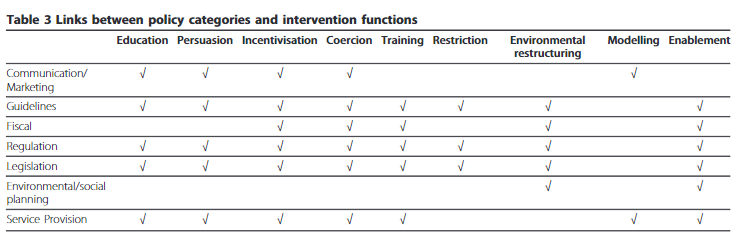

The methodology then moves from diagnosis to design. The Behaviour Change Wheel maps each type of barrier to the types of intervention and policy that can overcome it.

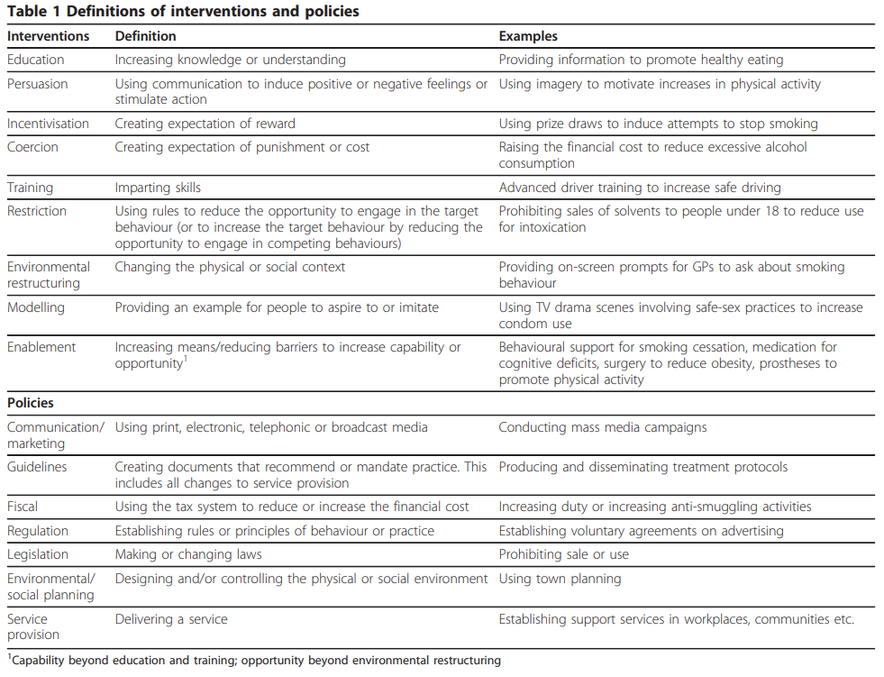

Three simple tables outline types of interventions and policies and map barriers (called ‘sources of behaviour’) to intervention and intervention to policy.

The Behaviour Change Wheel aims to make it easier to design appropriate and effective interventions and policies. After this, the methodology can move into delivery by implementing the chosen interventions. The Behaviour Change Taxonomy codifies evidence around different types of interventions and can be used to inform choices around interventions.

My initial takeaways

An important lesson learned from the course was that choices of behaviours and sources of behaviour need to be evidence-based. This not only means using a robust methodology, such as the Behaviour Change Wheel Methodology, to select interventions and policies but also means using evidence to define target behaviours and the capabilities, opportunities and motivations that enable or prevent them. With my User Researcher hat on, I felt this could be achieved through research with target audience members directly and/or with frontline staff.

In the Energise Manchester project we will need to work with members of the community to understand their behaviours relating to energy and barriers they face in taking action. We’ll also need to learn from those who are already delivering advice in the community, who have a lot of insight that we can use to inform and refine our approaches. This has been considered in the design of our project, as key partners and stakeholders like Manchester Care & Repair and Neighbourhood Health Champions have experience delivering advice and energy efficiency works in our target areas. As we work together on developing the Behaviour Change approach for the project, an evidence-centric approach will be crucial.

Another key takeaway from the course was that there are typically multiple and varied barriers or enablers for a given behaviour; it’s not often possible to design an intervention or policy that addresses all of them! This was a helpful reflection. During the course I practised carrying out COM-B mapping for a target behaviour and ended up with a long list of barriers: the temptation to try to solve them all is really strong! Going forward with the Energise Manchester project, it’s important that we focus our approach by prioritising those barriers that are most important to and impactful for our target audience(s).

This course was just the start of my learning journey about Behaviour Change. I’d recommend it as an overview of Behaviour Change methodologies, it has many practical examples that I haven’t gone into here. I will continue to capture learning about Behaviour Change throughout the Energise Manchester project here on this blog.